Although I never enrolled in an art class taught by Robert Marsh, he and I had a running conversation about art that lasted for decades. Often, our chats occurred in his Averett University studio while he was printing an etching or touching up an image with cray pas, his oil pastels. My appreciation for his brilliant work was evident; at least twelve of his pieces hang in my home.

Usually, I showed up at his studio just before he and I left to play golf. As eager as I was, however, I leaned to be patient while he added final touches to sizable paintings. Despite his casual demeanor, he seemed to be a perfectionist.

And not just with his art. Robert had a vision, a sense of what was good or bad, what was truly important versus concerns about normal fluctuations regarding life’s vagaries. His perspective, grounded in heartfelt caring, allowed him to guide his children without manning a whip of sharp criticism.

That same attitude, infectious as it was, created lifelong friends and admirers.

Around Robert, life was good, problems were surmountable, and laughter was plentiful. Even his critical remarks came across as being so even-handed that those of us who received them were appreciative, eager for more.

We trusted Robert that much, enjoyed our nicknames he conjured, and never stopped using. I was “Popper.” In return, I called him “Bro.”

That’s how I addressed him whenever I visited his studio unannounced. Often, he wasn’t there. That’s when I scribbled a message on the paper sheet used for sketching and comments that covered the large student’s table in the front of his large studio. Using a broken piece of bright colored cray pas, I’d write a one sentence note about how his absence had cost him my visit.

I knew he’d see it and would recognize it because I addressed my message to “Bro”; no one in his class would dare call him that.

That’s why it always felt to me that we were close as brothers. After all, I’d known him and his wonderful wife, Sandra, since before they had children. When their sons arrived, I marveled at their parenting skills, emulated them while raising my two daughters.

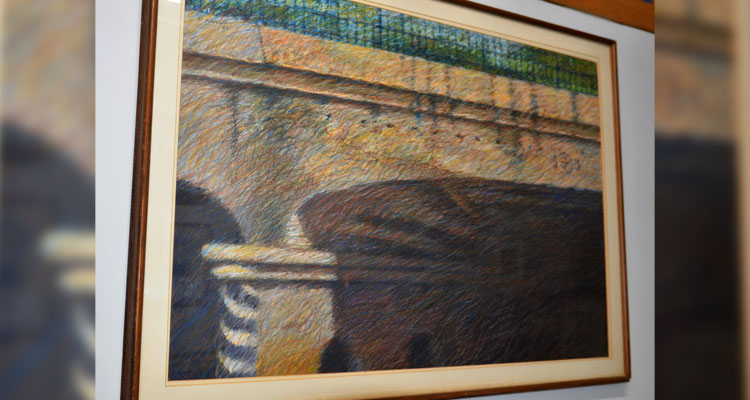

Life was special to Robert Marsh. Anyone who had seen his work knew that. Each image was vital, even his pastures and their cows; his etchings of historical homes appeared to portray memorable treasures. That same warmth caused the railroad’s trestle across Craghead Street to radiate as if in Robert’s spotlight.

But that wasn’t the only reason I bought his trestle painting. He had told me how much he’d wanted to portray that image, but couldn’t find the right way to approach it. That was on my mind when I photographed the trestle; I looked through my lens as if I were about to communicate what I saw to Robert.

That’s why I gave him my only copy of the picture I’d taken of it with my Leica.

Robert never gave it back. Chances are it’s in a box of sketches that now comprise mementoes of his life spent as an artist devoted to his craft.

As for the trestle picture, I admire it daily and consider it as a priceless memento of my days spent as Popper with a friend who was, indeed, my Bro.